What is of decisive urgency is the inclination of engaging all nuclear weapon states (NWS) in the debate over nuclear disarmament. The ensuing debate is often confined to strategic arms reductions between the US and Russia, thus making it a bilateral concern. The need of today to accentuate that nuclear disarmament is a collective task and all nuclear weapon states (NWS) are required to join their hands together towards attaining this goal. The prime focus of the “Project Base Camp” is that it provides leverage to all the stakeholders to think creatively and gainfully towards a nuclear weapons-free world. It gives a conceptual background for the immediate steps, which can be harmonized with those measures that are far-flung on the climb to the top of the mountain. In the “Project Base Camp”, the idea of proportional reductions will bear positive results whereby the dilemma of “you go first or I go first” can be addressed creatively and constructively [1].

Following this approach, different states will be disarming at varied rates so that at the end of a pre-determined time all states will have to remain content with the same number of reduced weapons. The primacy of nuclear weapons has to be de-valued as a currency of power or, in other words, nuclear weapons have to be de-legitimized. There has to be brought out a general disincentive towards nuclear weapons and in this task a normative vision of a nuclear weapons-free world (NWFW) would gear up the process significantly. Such delegitimization has to be coupled with doctrinal shifts and transformations where a comprehensive restructuring of NWS national security strategies and military organizations would be required in all probabilities. Further, the delegitimization processes will accentuate an ethical aspiration which would necessitate some sort of sacrifices from all stakeholders.

Eventually, the emergence of that situation is extremely significant in which the world succeeds in getting the elimination of all nuclear weapons. The most serious apprehension at that point in time would be the risk of someone amongst the stakeholders deceiving in the process. To appreciate the dream of a nuclear weapons-free world (NWFW) these problems need to be tackled right now. In this context, first the nuclear weapon states (NWS) and the non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) have to function in unanimity to enforce agreements in letter and spirit that are already concluded. This will necessitate stricter enforcement measures, and defiance of any sort need to be tackled more seriously and conclusively.

In the contemporary nuclear world scenarios, due to the awesome nature of nuclear stockpiles which nine states (the US, Russia, UK, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea) possess, decision-makers can be complacent in the presence of defiance, but in a world free of nuclear weapons any infringement has to be strictly checked by all means. Nuclear weapons can possibly be dismantled, but it is absolutely impossible to make zero the possessor’s scientific knowledge and technical know-how of making these weapons and therefore to debate that irreversibility is an ideal goal is very likely to enlarge the logic too far. In all such cases, transparency will be irrevocably required in their behavior and actions.

Conceptually, the “Project Base Camp” is pre-occupied with a number of issue-oriented challenges. First, the issue of shared responsibilities. For example, it can gain renewed momentum through the NPT Review Conference, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) framework or the special sessions of Disarmament in the UN. However what needs to be observed is that very often mutuality of shared responsibilities is confronted with a predisposition of biased responsibilities. Mutuality of shared responsibilities without structuring the individual responsibilities of different NWS and NNWS can culminate into elusive roles. Just like the discourse on global warming and climate change, the emerging issues of nuclear disarmament in the current situations encompass responsibilities especially on the part of permanent members of the UN Security Council to pursue negotiations in good faith to disarm. The US and Russia have to go ahead on both qualitative as well as quantitative cuts and others may join them later on the road to nuclear disarmament. The issues of how and when others contribute to the inputs of the US and Russia need to be ascertained.

Moreover an Asian discourse on nuclear disarmament is the need of the hour, especially when 21st century is marked as the century of Asia due to the rise of China and India as economic giants, without elaborating on regional instabilities and contradictions in the nuclear and other fields in the post-9/11 situation. The nuclear discourse in Asia should be one which is all-encompassing in nature and should not be limited to NWS, because the possession and proliferation of nuclear weapons in the Asian continent may not be free from the challenge of covertness adopted by the possessors and threshold proliferators. There can be threshold states possessing the technology to go nuclear and therefore their inclusion is very important.

Second, there are needs for removing functional ambiguities and implementing credible measures by the nuclear weapon states (NWS). This may lead to feeling among the NNWS that concrete steps are being taken to insure progress towards nuclear disarmament. Hence, substantial preparation has to be made for the success of the forthcoming NPT Review Conference in 2010.

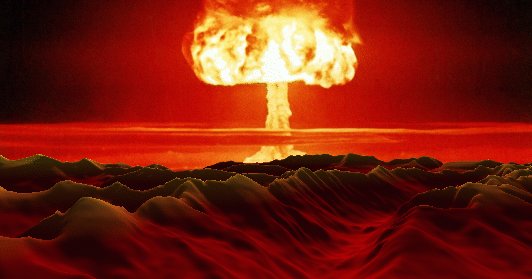

Third is the challenge of proportional cuts or numerical reductions of nuclear weapons and capabilities on the part of the states to reach the point “global zero”. The real challenge facing the world today is not of going ahead towards a fixed cut in the nuclear arsenals, but that of averting any employment of nuclear weapons anywhere by states or any non-state actors. Presently, the non-use of nuclear weapons can be a contentious issue in any nuclear debate, but making a distinction between civilian combatants and non-civilian combatants is an uphill task and, therefore, substantial steps to appreciate the moral issue on a relative basis should be discussed by analyzing different targeting plans.

Fourth, delegitimization essentially involves devaluing nuclear weapons as currency of power to deny their eventual use. The issue which then needs to be tackled is why the delegitimization has not witnessed progression with nuclear weapons. The simple reason is that nuclear weapons have provided exclusive political and security dividends by their internationalization as the currency of power for over six decades. The debate on nuclear disarmament in the past has been encapsulated in a very strict framework of a cut within some pre-determined time, or has been negotiated within the confines of moral overtures and therefore delegitimization needs to follow a balanced approach.

Fifth is the impinging uncertainty in the behaviors of non-state actors, especially after 9/11. In the post-9/11 situation, a new dimension of global insecurity is persistent on account of growing dangers of nuclear terrorism, whose cadres are not worried about earthly punishments [2]. The diffusion of technology and the smuggling of radioactive materials and items through illegal channels can increase the possibility of clandestine spread and use of “dirty bombs”. More significantly, the threat of nuclear terrorism looms large in South Asia, given the nuclear proliferation history in the region, especially Pakistan and AQ Khan connection, Al Qaeda network and the probable diffusion of nuclear materials and technology through illegal channels in the region [3]. In such situations, the Asian dialogue process on nuclear disarmament must involve the need of developing appropriate nuclear forensic techniques, as well as overcoming important strategic, political, diplomatic and organizational challenges in the region.

Lastly, an incessant challenge is that there will be changes in the global politico-strategic milieu and it remains uncertain how the “Base Camp” approaches will cope with such changes and consequential shifts to reach the top, i.e. the elimination of nuclear weapons. Notably, disinvention of nuclear weapons is not possible. But their possession and production can be curbed by building a global, comprehensive, non-discriminatory international regime of nuclear disarmament. This sort of regime should find a viable way to ensure de-legitimization and de-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

The US President Barak Obama’s decision to shelve the East European missile shield must be taken as a positive step towards the US-Russia shared mutuality and nuclear reductions in the years to come. The East European missile defense system planned under the Bush Administration in 2006 has been a major irritant in the US relations with Russia. This missile shield was to have been built by installing 10 interceptors in Poland and a radar system in the Czech Republic, which are East European nations at Russia’s doorstep and once under Soviet sway. Moscow has already argued vehemently that the system, if installed, would undermine the nuclear deterrent of its vast arsenal. In the US view, it was intended to protect Europe and the US from a rogue missile attack from Iran or North Korea and not to undermine Russia’s strategic deterrent.

Clearly, the US President Barak Obama’s decision to abandon the Bush administration’s missile defence plan came about because of a change in the U.S. perception of the threat posed by Iran. The Obama Administration perceives that short- and medium-range missiles from Iran now pose a greater near-term threat than the intercontinental ballistic missiles that the Bush plan addressed. Further, this decision can be taken at least in part as an attempt to conciliate Russia at a time when its support against Iran’s suspected nuclear programme has been irrevocably required. Given the world economic crisis, Obama’s pragmatic decision is appreciable, because this project would have given nothing but trouble for the US-Russian relations in this part of the globe.

Obama’s step is now going to serve as a predictable move of key importance towards a new strategic arms reduction treaty (START) to replace the soon-to-expire 1991 START agreement. Now the US and Russia can seek the ways through which the new START agreement will be completed on time, because the thorny issue of missile defense and its influence on the strategic balance has been removed for the time being. As a process of positive reciprocity to Obama’s decision of scrapping the East European missile shield, the available opportunity has contributed substantially to a warmer dialogue between Moscow and Washington and has induced Russia to offer reciprocal concessions as a specific “No” to the deployment of Iskander missile systems in Kaliningrad. That’s quite a significant step towards nuclear disarmament. The issues of how and when others contribute to the inputs of the US and Russia need be ascertained. Others will only join in when these two principal nuclear weapons states (NWS) cut their nuclear stockpiles and delivery systems drastically.

Follow the comments: |

|