Stakes and walls

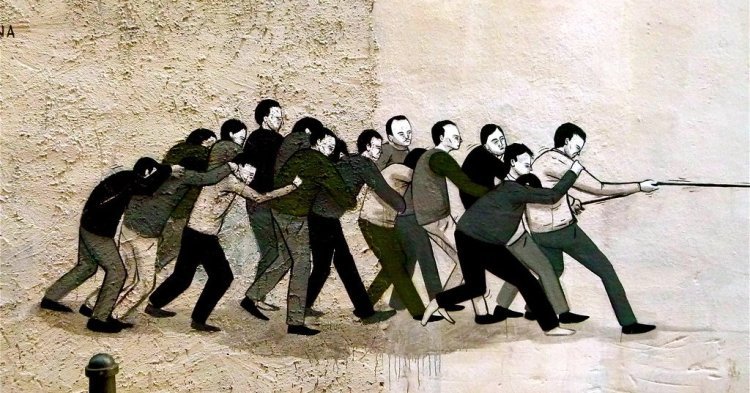

Written in 1968, while Spain still lived under the dictator Francisco Franco, “L’Estaca” called for mass resistance against the regime, urging listeners to “pull here” and “pull there” at the metaphorical stake that kept them pinned and unfree. Additionally, because Llach sang the song in Catalan (a language which was still banned at that time), the lyrics of “L’Estaca” were in themselves an act of rebellion.

Given this, it isn’t so surprising that the song has acquired a reputation over the years as a song of the Catalan independence movement. In fact, it has also been translated into many other regional languages, like Basque and Corsican, and performed with similar motivations.

But the appeal of the song goes beyond calls for secession or cultural autonomy. Ironically, although “L’Estaca” was banned in Spain almost immediately after it was first performed in 1969, it has since become one of the most widely known protest songs in the world. “L’Estaca” now boasts at least 37 different variations (including a Yiddish klezmer version !), and has made regular appearances at different demonstrations since the 1980s.

“It’s curious to see how, with time, this song has been sung in so many countries and in such diverse languages – and always as a symbol of popular rebellion”, Llach once said. “The most interesting thing that ever happened to me on account of this song occurred in the mid-1990s, when I took a trip to Poland. Almost everyone there thought of “L’Estaca” as a beloved Polish song, because the syndicate of Lech Wałęsa, Solidarność, had used Kaczmarski’s adaptation during the 80s.”

Indeed, when Llach arrived in Poland, “L’Estaca” had long since been transformed into a symbol of a different popular struggle. In 1978, after listening to a recording of “L’Estaca”, the Polish singer/songwriter Jacek Kaczmarski decided to create his own version, by keeping the song’s well-known melody but composing new Polish lyrics. The resulting song, “Mury” (or “Walls”), converted the anti-Francoist song into a hymn of resistance against Poland’s communist government. “Mury” quickly became the unofficial anthem of the Solidarność movement – despite its discouraging last verse, in which the protesters see the walls growing around them.

It may have taken a decade, but reality in Poland eventually turned out more rosy than in the song. The same can’t be said, though, of Belarus, where “L’Estaca” has also served as a rallying cry in the country’s ongoing pro-democracy protests.

The Belarusian version of “Mury” first appeared in 2010. More recently, the same song – as well as a Russian version – could be heard during the campaign rallies of 2020 presidential candidate Sviatlana Tsikanouskaya. Now, in the aftermath of the 2020 election, the song can still be heard in the streets of Belarus, alongside other anthems both old and new. The Belarusian State Philharmonic Society even performed a rendition of the song while on strike recently.

A song of solidarity and interconnection

In the Belarusian version of “Mury”, the last verse ends the song with images of triumph (“we will forget the cockroach”, it says, referring to Belarus’s dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka). But the anti-autocratic energy of “L’Estaca” clearly has no bearing on the stability of autocratic regimes. Although things turned out relatively well in Spain and Poland, the future of the protests in Belarus—now over 50 days long—is still far from certain.

This is also apparent from the song’s other appearances beyond Europe, such as in the Tunisian Revolution (“Dīmā, dīmā”, or “Always, Always”), or at the protests in Moscow in the early 2010s (“Stjeny ruchnut”, or “The Walls Will Fall”). If what happened in Russia is any indication, in fact, protestors in Belarus may have a long, hard road ahead of them. After all, how well is Russia’s “Snow Revolution” remembered in the West now ?

But what may be more interesting than any balance sheet of this kind are the sorts of interactions that “L’Estaca” exemplifies. Although Spain can seem a pretty long way from Eastern Europe, the two are much more interconnected than they might appear at first. Indeed, not even a closed-down Schengen Area would ever be able to keep them fully apart.

There have always been trends in Southern Europe that have influenced trends in Eastern Europe, and vice versa. Towards the end of the 19th century, Catalan autonomists drew inspiration from debates about national minorities in the Habsburg Empire – and in particular, from the work of Czech nationalists. And around the turn of the 21st century, the Spanish democratic transition served as a valuable point of comparison for reformers in Europe’s new post-communist societies, especially Poland and Hungary.

At a time of deepening divisions between North and South, West and East, “L’Estaca” – and all its offspring – should remind us that nothing in Europe truly occurs in isolation. Europeans have more in common with one another than they might think, and they have more of a capacity to affect one another than they might imagine. The journey of “L’Estaca” over the years shows that pro-democratic protest movements face similar struggles everywhere, and that, even if dictators can draw inspiration from one another, so too can the protesters.

Suivre les commentaires : |

|