In spite of this outcome being largely what the polls had been predicting throughout the campaign the heavy victory for the Yes side was still considered surprising. Irish referendums on social issues have tended to be notoriously bitter and divisive in the past, in addition to being extremely close. A referendum on legalising divorce in 1995 passed with only 50.28% of the vote (with a Yes margin of victory a mere 9,114 votes nationally). Later, in 2002, a vote on tightening Ireland’s very strict abortion laws was rejected with 50.42% of the vote against – a margin of 10,556 votes and with virtually the same geographic split nationally. Few expected this referendum to play out particularly differently to those contests. In particular the divorce referendum haunted the Yes side, where the socially liberal side of the contest saw large poll leads that gradually dwindled to almost nothing by polling day.

The referendum was not actually a commitment of the Christian Democratic Fine Gael Party and Social Democratic Labour Party coalition when they entered government in 2011. Labour was supportive, however the more cautious Fine Gael instead put the issue to the Constitutional Convention, a joint citizen and politician assembly that would consider a large variety of political and societal reforms. This assembly, in turn, suggested that Ireland adopt the issue into a law and as the Irish court system had previously interpreted the constitutional definition of a family as applying only to a man and a woman this meant the change would require a referendum – like any other constitutional change in Ireland.

All political parties supported the Yes side of the campaign, however undoubtedly the main force on the Yes side was the civic society organisation ‘Yes Equality’ (YE), an umbrella organisation consisting of the Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN), Marriage Equality (an organisation with an easily guessed goal) and the Irish Council for Civil Liberties. The No campaign was dominated by the Iona Institute, a socially conservative think-tank, and the civic society group ‘Mothers and Fathers Matter’ (MFM).

Irish referendum campaigns have been strongly shaped by the Coughlan and McKenna Supreme Court judgements, which stipulate that governments cannot fund or advocate for a side in a referendum and that the state broadcaster must be ‘balanced’ in their coverage of the issue, which has generally been interpreted as giving both sides of the issue equal time on the airwaves.

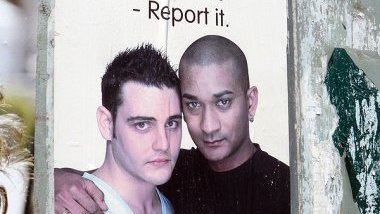

Driven by an extremely large number of campaign volunteers, with some Dublin organisations routinely acquiring fifty volunteers a night to campaign, and over a hundred by the last few days – numbers any Irish political party would give a great deal for – YE ran an extensive ground based campaign, aiming to knock on as many doors nationwide as possible and by highlighting how a Yes vote was a vote for family values and inclusion. MFM went for a more traditional referendum campaign in Ireland – focusing much of their time on a national poster effort and on the airwaves. However, the somewhat less charitable view of this campaign is that they simply lacked the groundswell of local support in order to compete with YE on door-to-door campaigning. Being involved in the Yes campaign was a unique experience. It was very unlike previous political campaigns in Ireland. Very few volunteers had previously been involved in politics at all, but fairly soon became grizzled veterans of a very personal campaign. No voters rarely explicitly told you that they were voting No. Rather, they emphasised firmly that they had made up their mind, that there was no argument that you could use to sway them, before very quickly closing the door. If they gave a reason it tended to be that they did not trust gay people with children. By contrast Yes voters tended to be very enthusiastic – showing you their polling card and assuring you that they knew how important actually voting on the contest was.

While the general contours of the vote were similar to past referendums on liberal and European issues, there were some differences. Notably, working class areas of Dublin were noticeably more in favour of equal marriage than their middle class counterparts, who are normally at the forefront of any socially liberal cause. While middle class areas of Dublin were not poor by national standards (and indeed some were excellent) they were noticeably more reticent to support, and were significantly more likely to be wary on the doorsteps of the proposal. This was particular true of the more ‘middle’ class areas, with older populations and without huge reserves of wealth and education, but still definitely prosperous. By contrast in Dublin’s most deprived areas the positivity towards the Yes campaign was nearly overwhelming. Looking at the geography of the result this seemed to be borne out – with worse off Dublin Central, Dublin South West and Dublin South Central among the most overwhelmingly supportive, while Dublin South – the wealthy heartland of golf club memberships and support for Europe, had among the lowest support in Dublin. While against the usual pattern of such issues, this would have been in no way surprising to those on the campaign and actually talking to real voters.

The extreme public interest could be seen in the high turnout – 60.52% is well above European treaties and not particularly far below General Elections. The anticipation of the result the following day turned effectively turned Dublin into a spontaneous street party – no doubt helped by the large influx of young people arriving home to vote.

They, at least, were certainly celebrating not only equality but maybe also another nail in the coffin of Ireland’s conservative Catholic reputation. Whether Ireland will follow this with further liberal reforms, or whether Germany and Italy follow suit with marriage equality, remains to be seen.

1. On 12 June 2015 at 18:18, by duodecim stellae Replying to: Irish Marriage Equality Referendum

Replying to: Irish Marriage Equality Referendum

The Irish vote outcome has been a really big issue in German media. Now many people are arguing that we need gay-marriage here in Germany. So far we only have registered life partnerships, which are not 100% equal to marriage (no adoption right).

Follow the comments: |

|