Trade in Chemicals and related products is a no-less-complicated issue than agricultural products. In 2005, the Patent (Amendment) Act 2005 was passed by the Indian Parliament to amend the Patent Act 1970, after pressure to meet India’s obligations under the TRIPS Agreement [1] of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The major difference relevant here is the removal of Section V of the Act, paving the way for product patents in the area of pharmaceuticals and other chemical inventions.

As it stood after the amendments made in 2002, Section V had provided that, in the case of inventions being claimed relating to food, medicine, drugs or chemical substances, only patents relating to the methods of processes of manufacture of such substances could be obtained. In other words, only a process patent could be obtained, as opposed to product patents. Product patenting was not granted on such inventions. This meant that if a company invented Medicine X to cure a disease using process Y, that company cannot claim a patent on Medicine X, but can do so for the process Y.

This resulted in a situation where a reverse-engineering mechanism was widely adopted to develop the same medicine and drugs with slightly or substantially different process, leading to a sort of ‘copycat’ business. This allowed a few pharmacy companies to grow into global players, reducing the barrier to entry for new firms. As a result, competition increased, and it became increasingly difficult to establish monopolies. This led to further drops in medicine prices.

An internationally unpopular move

While this reduced the prices of pharmaceuticals, drugs and chemicals in the market overall, pressure soon built internationally as Section V was not in compliance with the TRIPS Agreement. However, it seems that in practice, Section V has not been entirely removed.

In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court denied a patent application for Gleevec, an important treatment for leukaemia made by Novartis. Here, in Novartis v Union of India and Others, the court’s decision relied on section 3(d), which prevents companies from ‘evergreening’ [2] their drug patent estates and requires proof of enhanced efficacy for new forms of existing compounds in order for them to be patentable. It pointed to Novartis’ claim and rejected its case:

“In the application it claimed that the invented product, the beta crystal form of Imatinib Mesylate, has (i) more beneficial flow properties: (ii) better thermodynamic stability; and (iii) lower hygroscopicity than the alpha crystal form of Imatinib Mesylate. It further claimed that the aforesaid properties make the invented product ’new’ (and superior!) as it ’stores better and is easier to process’; has ’better processability of themethanesulfonic acid addition salt of a compound of formula I’; and has a ’further advantage for processing and storing.” [3]

The situation is not unique, as India has granted compulsory licenses to other cancer drugs to allow generic drug manufacturers to make these drugs “with impunity” even if the drug has been patented by a company [4] [5]. The explanation is that this would ensure that expensive drugs are available at affordable prices to the poor. However, some have found that cheap foreign drugs also face such treatment, solely because they are not ‘home-made’. [6]

India is in a unique position in terms of chemicals and pharmaceuticals. While it is known as the “pharmacy of the developing world”, its refusal to recognise patents, which seems to be embedded in sections of the 2005 Patent (Amendment) Act beyond the removed Section V, could and has become an issue with the EU. Pharmaceutical companies have been pressuring the EU to demand stricter rules on intellectual protection, including data exclusivity protection measures and ‘ever-greening’. Here, the pressure on India also comes from aid organisations such as Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières and UNITAID.

Intellectual property and access to life-saving drugs

In the context of negotiations between the EU and the Andean region, the EU–Latin American and Caribbean Alliance for Access to Medicines Network carried out impact studies assessing the effects of intellectual property rights protection in FTAs. According to these studies, the extension of the patent and trial data protection would significantly increase medicine spending. The negotiations with the Andean region did not include provisions on data exclusivity and data protection, but in the case of India, the impact of such provisions would be substantial and would especially affect the poorest part of the population. [7]

In other words, should India comply with the EU’s demands for intellectual property, including provisions on data exclusivity, the social impact would be devastating as much of the population would find themselves unable to afford medication. This issue has been brought to the European Commission, which responded by issuing a Q&A document on access to medicines in the negotiations.

The document states that the intellectual property provisions in the FTA will not weaken ‘India’s right and capacity to manufacture and export life-saving medicines to other developing countries facing public health problems’. It adds that, although the Commission believes in the importance of data exclusivity, it will be flexible and will consider the position of India as producer of essential generic medicines. Furthermore, the Commission declares it is ‘doing a lot to promote access to medicines in developing countries’, through funding projects and programmes; participation in the World Health Organization; the WTO debate on TRIPS concerning public health; and a tiered pricing mechanism for the supply of cheaper medicines to developing countries (which allows EU companies to sell products much more cheaply to developing countries).

The former European Commissioner for Trade, Karel de Gucht, also sent two letters in response to Médecins Sans Frontières, stressing that enforcement measures on intellectual property protection is to tackle products infringing copyrights, not generic medicines, and that the provisions of the EU-India FTA would not end up targeting trade in generic medicines.

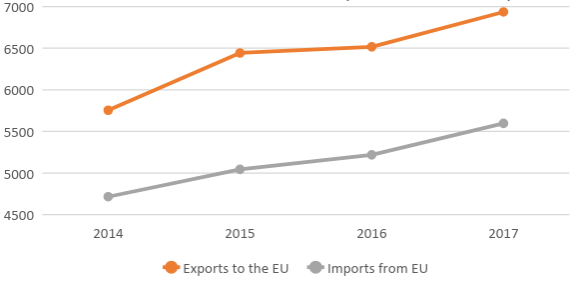

The EU’s obligation in this matter seems to have been stressed time and again. At the 12th EU-India summit, the head of the EU Delegation again addressed an open letter, affirming that the EU “recognises India’s right to issue compulsory licensing for medicines and has no intention of weakening [its] capacity to manufacture and export medicines to other developing countries”. This seems to be reflected in trade statistics, as the ability of one party to recognise the other’s concerns has resulted in substantial trade in chemicals and related products.

Exports in chemicals and related products are more than twice the size of those for agriculture, while that figure is seven times higher for imports. However, it must be noted that this is only possible as this sector seems to be less of a sore spot for the EU, unlike agriculture, which is equally contentious for both parties. It is far more likely, given India’s experiences with other free trade agreements, that parts of the agricultural sector may be excluded from the agreement, while agreement in other potentially contentious sectors depends largely on the sensitives of both parties and the concessions that each is willing to make.

Follow the comments: |

|