From Provence to Alsace, families marked by the wars

On my mother’s side, my great-grandfather (my mother’s grandfather); originally from Sartène (South Corsica) died during the Second World War. His wife Julie then left Corsica with their five children (including my grandmother), and moved to La Ciotat, in French Provence. Working as a nurse in a hospital, she took care of Pierre Gay, a wounded French soldier. They married after the war, and Pierre adopted and raised the five children as his own. Twenty years later, one of these five children, Ange Panzani, fought in another war: having his heart broken by a woman, he decided to enrol in Indochina. He came back alive, but wounded and traumatised.

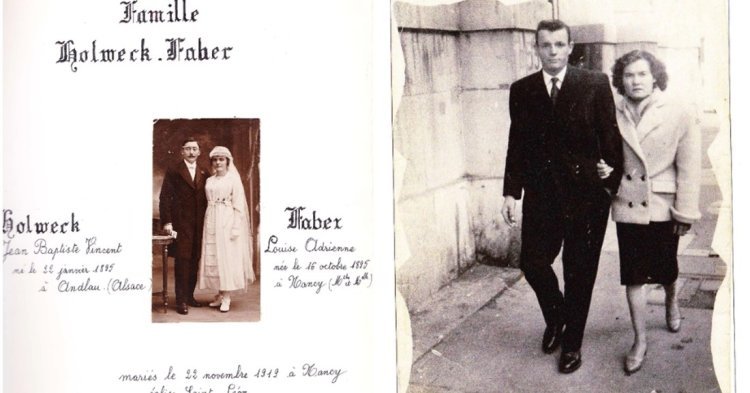

Meanwhile, on the opposite side of France, the region of Alsace-Moselle had been annexed by the Germans in 1871. When the First World War started, men from Alsace-Moselle were thus enrolled in the German army. They were called the “Malgré-nous” (literally, “despite ourselves” or “against our will”). Nevertheless, some managed to desert the German army and joined the French one. However, considered as Germans by the French administration, they were able to serve France only through the “Légion étrangère” (the French Foreign Legion). This was the case of Jean Holweck, my great-grandfather (my father’s grandfather). On the front, he met a nurse named Louise Faber. They married after the war, and had five children, including my grandmother (my father’s mother).

During the Second World War, Alsace-Moselle was annexed again, this time by the Nazis, and men from Alsace-Moselle were forced to enrol in the Wehrmacht, creating a new generation of “Malgré-nous”. But like last time, some refused to serve under the Nazi flag and managed to desert. From 1943, when the Nazis began to lose the war, they started roundups of teenage boys in Alsace-Moselle to enrol more and more soldiers. Roland Weber (my grandfather, my father’s father), 17 years old, could have been grabbed like this by the Nazis, and his parents looked for a solution to save him. Working as cookers for a mine, they were also hosting two Belgian miners in their house. After learning about their son’s situation, one of the miners gave his passport to my great-grandparents, they falsified it, and their son was able to flee to Belgium, where he lived in forests and barns while working as a farmhand. When the war ended, he came back to Moselle, where he met Anne-Marie Holweck, daughter of Jean. They married and had two children, including my father.

When wars are over, space for a glimpse of crossings and cultures

Free from wars, the rest of the story is about encounters and crossings. In the 1950s, in Provence, Marie-Antoinette Panzani, daughter of Julie and adoptive daughter of Pierre, met Aimé Martina, son of Italian immigrants. Pierre opposed to his adoptive daughter marrying an “Italian” (which is ironic enough considering that he had himself married a Corsican woman named “Panzani”). French Provence indeed knew a wave of Italian immigration in the 1920s, and some locals called the Italians who settled in the region “babi”, a pejorative Provençal term meaning “toad”. But Marie-Antoinette married Aimé anyway, refusing at the same time to move to Denmark with the family of which she was the housekeeper. They had four children, including my mother.

I mentioned Provençal, so let me open a parenthesis about regional dialects in France. The Provençal dialect is a variety of Occitan, spoken in Provence in the South of France. A minority of people speak it fluently (as is unfortunately the fate of many regional dialects in France), but some words have been incorporated into the everyday language. The same goes with the Alsatian dialect. As they were living in the town of Nancy (Meurthe-et-Moselle) in the 1940s, my grandmother’s parents sent her and her sister to the Alsatian countryside, for them to be safe in case of gunfire happening in the town. When they came back, they spoke better Alsatian than French. By the way, no need to come from another country to be mocked for your origins. The Alsatian accent of my father was “discordant” when he studied in Paris, and same goes with my mother’s Provençal accent when she moved to Bordeaux.

Later on, one of Aimé and Marie-Antoinette’s daughters (my aunt, my mother’s sister), met a man originally from Auvergne, arriving in Provence to work in a shipyard after working as an oyster farmer in Ile de Ré. The lack of work in Provence then made them move to Bordeaux, where my mother joined them. In the meantime, my father, son of Roland and Anne-Marie, after studying in Nancy, Paris and Evanston (Illinois, United States), arrived in Bordeaux to work as an engineer. This is where my father, grandson of Jean Holweck, and my mother, granddaughter of Julie Panzani met. My brother and I are, for now, the last generation of the story, free from wars but certainly not from mobility.

Call me cheesy or outdated if you like, but yes, ’Europe is peace’

We can all suppose that most our grandparents or great-grandparents somehow knew the war, on the front or as civilians. But when you actually learn exact stories and names, which are your ancestors’, history takes on a new dimension. “First World War’s soldiers”, “war widows” or “Malgré-nous” become “my great grandparents” or “my grandparents”. For other people, it might be “Senegalese Tirailleurs”, “resistance fighters”, “deported Jews” or “collaborators”. People on both sides of my family knew the wars, experienced them directly and personally, in different ways. This obviously reminded me of history, gave me food for thought and some humility.

Thus, I would like to address the “moral” of this story to these nationalist Europhobic who wholeheartedly proclaim that a united Europe (whether you call it the former European Communities, the current European Union or even the “old dream” of a federal Europe) has nothing to do with peace on the continent. Read history books, look at your own history, do your duty of remembrance, and show some respect towards the people who suffered from the wars between the European countries, before they built together a political model which, though being improvable, allowed to avoid the repetition of wars on the continent. I wrote this article chronologically, and the cut between the two parts, between the end of WWII and what happened next in my family’s history, also historically corresponds to the beginnings of the European construction. Since then, my family, as many other European families, did not suffer from wars on the continent anymore.

I address it as well to the (numerous) pro-Europeans I have heard saying “Oh come on, let’s not keep bringing up ’Europe is peace’, this so cheesy, Europe has other issues today, let’s talk about something else”. Yes, Europe needs to address other issues, to face new challenges and to develop new narratives. But its fundamental, original, historical narrative and raison d’être is peace. I don’t see why bringing up new narratives and answering current challenges should prevent us from also remembering history. Call me cheesy or outdated if you like. But would you be so haughty in front of your own grandparents?

Follow the comments: |

|