The Spitzenkandidaten and ‘La République en Marche’: a foreshadowed disenchantment?

If Emmanuel Macron and LaREM demonstrated a certain will to Europeanise the European elections by defending the transnational lists, their position regarding the Spitzenkandidaten process did not stand out by their enthusiasm.

The first time he spoke on this subject during his speech at La Sorbonne University in September 2017, Emmanuel Macron expressed quite a lukewarm opinion about the Spitzenkandidaten, if they were not closely linked to the introduction of a transnational list:

“To all the major political parties that explained us that it would be astounding to have a Spitzenkandidat for the European Commission, that wanted to Europeanise these election, I’m telling them: Fully extend the reasoning! Don’t be afraid! Have real European elections!”

This statement suggests that the Spitzenkandidaten would only be relevant if associated to a transnational list, which at best is a lack of understanding of the system, and at worst pure and simple bad faith. As a reminder, the Spitzenkandidaten are lead candidates appointed by the European political parties, and they’ve never needed a transnational list to exist. Regardless of whether one considers that a transnational list would be an “added value” to the Spitzenkandidaten process or not, the link between the two is far from being exclusive.

Emmanuel Macron then developed his position when he spoke in front of the European Parliament in April 2018. The French President of the Republic would not be against the Spitzenkandidaten, but would have preferred they are accompanied by a transnational list (as a reminder, the European Parliament voted against such lists in February 2018):

“I believe in the Spitzenkandidat, I think it is a very good one. (…) I consider as a progress that the existing political families propose a Spitzenkandidat. I consider it was even more democratic to fully extend the logic and to have a form of European expression and a possibility for the beginning of a European demos. And if we had been coherent until the end, this President, this Spitzenkandidat, would have been the lead candidate of a European party. I do not oppose this at all. (…) If we want to start having a federal thinking, we must go towards transnational lists, which are fundamentally real European lists (…).”

Opposing Spitzenkandidaten is either opposing European democracy, or not understanding it

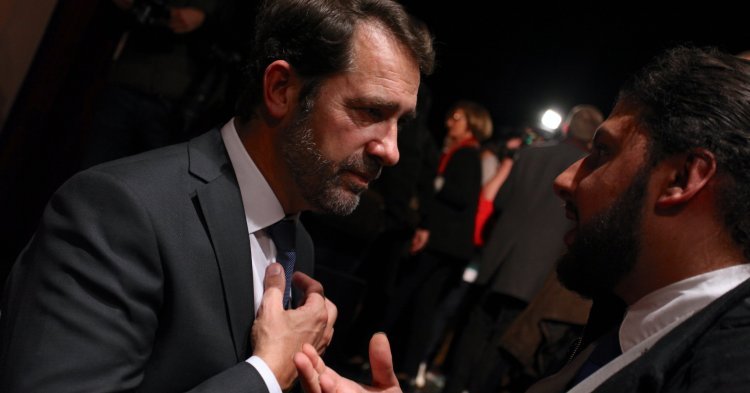

Emmanuel Macron and LaREM’s tepidity regarding the Spitzenkandidaten process would thus be due to the disappointment following the decision of the European Parliament to reject a transnational list, but they would still support the principle? Judging by the declarations of Christophe Castaner in front of supporters on 4th September, it seems that LaReM is at best divided and at worst against the Spitzenkandidaten, the party’s chief executive having called them a “democratic anomaly”. He would have explained that MEPs about to leave office that choose their next leader would amount to a Parliament that would choose its next government. Such remarks show that he “did not understanding anything of European democracy”, or parliamentary democracy. “MEPs about to leave office” are not the ones choosing their next leader (and by the way, the Commission President is not, in any way, the “leader” of the European Parliament), but the Heads of State and Government who appoint a candidate by taking into account the results of the election (so logically, the Spitzenkandidat of the party which arrived first). And this candidate can take office only if he is then elected by the European Parliament (by the MEPs following the elections, and not the ones “about to leave”…).

The Spitzenkandidaten are absolutely democratic. They give the European citizens an indirect vote on the Commission Presidency, by presenting candidates known in advance, during the campaign, and who represent a party, ideas, a programme, a vision for Europe. All in all, they are actors of the European project and of European democracy. Especially as the results of the elections have to be taken into account by the European Council (i.e. the Heads of State and Government of the EU member states) when they propose a candidate to the European Parliament, which elects the candidate. In short, the European citizens’ votes will determine the appointment of the leader of the EU executive branch, elected by the Parliament, itself elected by direct universal suffrage. Which is peculiar to a parliamentary executive (but Christophe Castaner, used to a presidential regime, might have difficulty understanding this?).

Like it or not, the Spitzenkandidaten are already running

Fortunately, whether some like it or not, the Spitzenkandidaten are already running. Manfred Weber recently announced his candidacy as Spitzenkandidat of the European People’s Party, and would be supported by Angela Merkel, while Michel Barnier would consider it. More broadly, four European parties (the EPP, the ALDE, the S&D and the Greens) have already announced that they would present a Spitzenkandidat, as well as how they would be appointed within the party. European democracy thus cannot be undermined by the mere declarations of a national party’s chief executive, although they are unpleasant ones.

Moreover, the European Commission, executive organ of the EU, is often pointed out as a technocratic and unelected body. It is true that the European Commissioners are unelected (just as the ministers of a national government), but thanks to the Spitzenkandidaten, the Commission President is elected by indirect universal suffrage, and the Presidency candidates are known during the European campaign (instead of arising from intern and opaque arrangements between the Heads of State, as it was the case before the Lisbon Treaty). If an election of the President by direct universal suffrage would indeed be more desirable, the Spitzenkandidaten already are a considerable democratic progress.

Instead of attacking the Spitzenkandidaten, LaREM just as the others should better focus on the real urgent democratic challenges of the European campaign: tackling populist and Europhobic parties (personally, I don’t want to see ever again the Front National winning the European elections in France), enhancing the visibility of European political parties and their Spitzenkandidaten, improving the media coverage of the campaign and of European issues, getting the European institutions closer to the citizens, and more.

We, young Europeans and activists, have to make European democracy’s voice heard and, regardless our political affiliation, to push the political parties into raising European matters during the campaign.

Follow the comments: |

|