Populism is not a clear ideology: it can be left-wing or right-wing. This is mainly a political phenomenon which relies on specific means of action (such as speeches, values…) aiming at overthrowing the “elites”, the established order, and representative democracy as we know it today. At the European level, this populism threatens the European institutions and risks casting a shadow over Europe’s future.

Populism is a paradoxical political phenomenon. First, because it is essential to democracy: it promotes popular sovereignty over the state and its institutions. To be populist is to assert that the power of the people must prevail over the institutional power of the state, and not the contrary. So why has the word taken such a negative connotation? Today, the political movements labelled as “populist” are characterised by a frank opposition to representative and parliamentary democracy as we know it today in Western Europe. Populists are often demagogue: they flatter popular passions to reach power.

The “people” against the “elites”

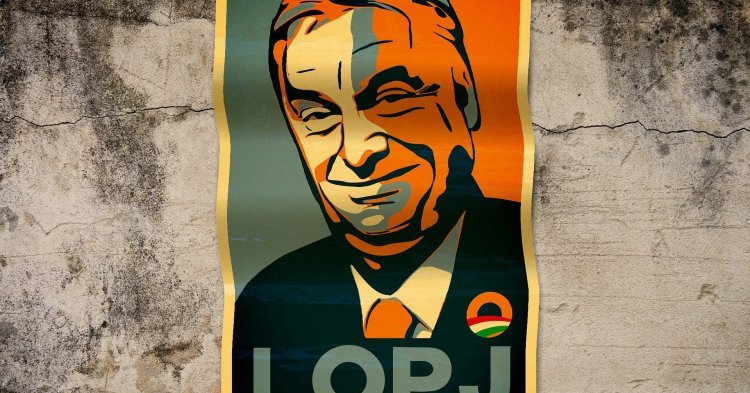

Populists assert the power of the “people” against the national and European “elites”. They denounce the established elite which they consider as “corrupted and “disconnected” from the people’s needs, and they describe themselves as “anti-system”. Their solution is to oust these elites from power – violently or not – and to restore the “people” at power.

For instance, the left-wing Spanish political party Podemos, led by Pablo Iglesias, prefers “normal people” to Brussels’ “technocrats”. In its speeches, the party calls for a return to a popular unity in order to make its sovereignty respected. It criticises liberalism and campaigns for a citizen control over the institutions, the economy and the taxes.

The discourse: simplistic, flattering and abstract

The populists flatter popular passions to legitimate themselves and to differ radically from traditional political parties. Their message is often simplified, excessively repeated, and relies on a deformation of the reality to legitimate their speeches. The populist parties then become “catch-all”: they feed on public discontentment to reach power. But seeking to gather all the discontents can lead to contradictory programmes, which can even be inapplicable economically or politically.

For example, in Jean-Marie Le Pen’s speech on 1 May 2017, we can find the themes of the National Front’s campaign: “homeland”, “work”, “nation”, “nationalism”… In order to convince, Jean-Marie Le Pen plays on emotions, and above all on fear (“cowardness”, “sacrifices”, “tragic”, “abominable”, “catastrophe”…).

In the European Parliament: movements against Europe in the heart of Europe

For the past years, populist parties have been rising in the European Parliament. Today, the most right-wing, conservative and Eurosceptic political groups at the European Parliament represent 172 seats out of 751, including the parliamentary groups European of Nations and Freedoms (ENF), Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD), and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), as well as the non-attached (i.e. MEPs having decided not to join any political group). Among these MEPs, most come from national populist parties. In France, the “navy blue wave” [1] multiplied by eight the number of National Front’s MEPs (registered either as National Front or non-attached members), passing from three in 2009 to 24 in 2014 (out of 74 French seats).

Populists are the symptom of the social malaise and of the lack of communication between the European institutions and their citizens. These movements are waving Euroscepticism (or even Europhobia) as the flag for the liberation of the peoples, which becomes a major issue in the European elections.

Why are anti-European parties sitting in the heart of Europe itself? Their legitimacy lies in European citizens’ growing votes for their programmes, at least the ones who actually go to the polls (the European elections are the ones where abstention is the highest). In the end, these populist parties remain a noisy minority: despite their electoral success, they represent 22.6% of the votes. Their “catch-all” capacity put traditional parties in a difficult position, especially as they are lacking political renewal. Finally, the populist movement uses diverse strategies, which can even be contradictory: if many claim to be Eurosceptic, the ruling populist party in Poland, Law and Justice (PiS), adopted a pro-European strategy in order to gain seats in the European Parliament. The PiS even chose “Poland is the heart of Europe” as its slogan.

Why such a rise?

The different crises of the past years have widely contributed to arousing European citizens’ fears. The 2008 financial crisis and its austerity politics, the unparalleled migratory crisis mismanaged by the EU, or the terrorism at the heart of the continent are causes of the identity and political tensions revealed by the votes. The populism of anti-European parties has played on the fear and on difficulties felt by the citizens. In front of the Brussels’ image of a technocratic elite disconnected from the people’s reality, these parties at the margins of the partisan system have been able to practice their demagogy and so to cling to power. The high abstentionism at the elections also plays in their favour.

A long-in-coming answer from “traditional” parties

Faced with discontent of a part of the population, the response of the European governments and of the European Parliament’s groups seems inefficient. The “traditional” parties, whether left-wing or right-wing, remain on the defensive, and lose their voters in favour of a more aggressive and polarising speech.

On European level, the arrival of anti-European elected representatives within the European Parliament represents a systematic blockage of the decisions. The minority groups would become coalition partners, which would oblige traditional parties to rule with them. Moreover, the populists represent a “dead weight” for Europe, which would accentuate the European institutions’ paralysis. In front of these challenges, the European elections of 23–26 May 2019 represent a crucial moment in the construction of the European project.

The proportional system of the elections indeed favours anti-system parties, but previously allowed for groups such as the Greens to gain prominence. Let’s hope a European awakening in front of the structural rut that a consolidation of populist groups within the Parliament will cause. It should be recalled that the legislative body of the European Union directly acts upon the citizens’ lives: in order to best represent their interests, it is necessary that the citizens massively participate. The European democratic dialogue cannot exist when a large part of the population does not commit to it.

Follow the comments: |

|