So far, however, things are not looking good. The sigh of relief breathed by Brussels since Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were elected in November caught in their throats on January 6th. The first week of the new year bore witness to an unprecedented violent insurrection and attack on the U.S. capitol. These events dashed most of any remaining hope from EU and Member State leaders that the United States would quickly recover, leaving the last four years as “blip” in its record. Watching a violent mob, egged on by the sitting President, violently attack the U.S. Capitol, endangering the lives of congresswomen and men, their aids, and, in some cases, even their families, along with Vice President Mike Pence, to interrupt the certification of President-elect Joe Biden seems not to be a great sign for what is to come.

The United States is not, however, the only one whose democracy and rule of law is clearly under threat. As Portugal takes on the presidency, the EU is internally divided regarding these constitutional values themselves.

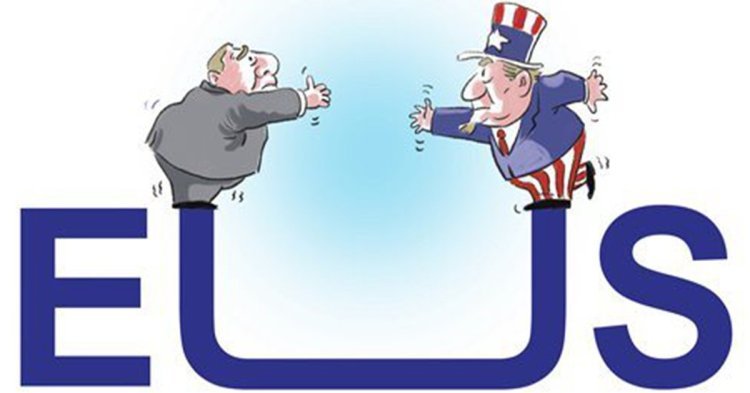

Perhaps facing similar internal threats will help these administrations in their quest to successfully initiate relations with one another and revitalize and restore faith in the transatlantic relationship. In addition to threats to democracy from rising populism and authoritarianism, other commonalities the administrations face are increased internal polarization, continued recovery from COVID-19 and the vaccination of their respective populations, as well as building back better regarding resilience, green, and social (fighting inequality) policies.

On the international stage, both administrations will face a variety of issues centered around their own declining global power and a fraying international system. These realities are linked inherently to the rise in other geopolitical actors whose disruptive tactics undermine international and internal stability and cooperation and help create and exacerbate general international turmoil. Also under threat are years, if not decades, of progress in poverty and inequality reduction work undergone by both the US and EU. Multilateralism is also in duress, although slightly less so with Biden’s intention to reaffirm the US commitment NATO’s mutual-defense guarantee, bring the US back into the Paris Agreements, stay in the World Health Organization, stop disrupting the World Trade Organization, and sign on to the EU negotiated Iran nuclear activity deal. Post-Brexit relations with the UK are also front and center on both administrations’ to do lists, as is countering China’s economic and political influence.

Elaborating a bit on these referenced commonalities, the action lines highlighted in the programme for the Portuguese Presidency are building as follows:

1. “Resilient Europe: Promoting recovery, cohesion and European values”

2. “Green Europe: Promoting the EU as a leader in climate action”

3. “Digital Europe: Accelerating the digital transformation for citizens and businesses”

4. “Social Europe: Enhancing and strengthening the European social model”

5. “Global Europe: Promoting a Europe that is open to the world”

These action items are meant to work on three major priorities: promoting recovery through and with the twin transitions of climate and digital; ensuring these transitions are inclusive and fair with a focus on social policy; and strengthening Europe’s relationship with the world via its own strategic autonomy. Similarly, the Biden-Harris transition’s priorities are focused on building back better, with the following four key points:

1. COVID-19: science, public health professionals, government trust, transparency, commonality, and accountability

2. Economic Recovery: through stimulus checks, job creation, taxing corporations and the wealthy, student debt relief, among others

3. Racial Equality: “The moment has come to deal with systemic racism”

4. Climate Change: “leading the world to address the climate emergency and leading through the power of example”

Other key points for day one and the first 100 days of Biden’s presidency include immigration and criminal justice reform as well as repairing alliances and planning a global Summit for democracy.

Both administrations have repeatedly highlighted the intention to work together. Even two years ago at the Munich Security Conference Biden took the stage after a very anti-transatlantic address from US Vice President Mike Pence and promised that the isolationist America first policy harming the US’ relationships with its closest allies would pass: “We will be back”. His foreign policy experience and relationships with US allies that could help him repair the damage of the last four years is something Biden emphasized throughout his campaign.

Directly after Biden was determined the winner of the U.S. presidential race, congratulatory messages came pouring in from across the EU, seeping with relief, and ridden with terms of friendship, partnership, and togetherness. A month after the election, the European Commission and High Representative put forward a proposal for a new transatlantic agenda – focusing on health, democracy, technology, trade, and climate – which the Economist reported a source close to Biden says substantially aligns with the incoming US administrations’ thinking.

In terms of the Portuguese presidency, one of the bullet points under action point 5 of their program is to “[s]trengthen dialogue with the United States, a strategic partner in all fields, with a view to exploiting the full potential of transatlantic relations”. Another example is Portugal’s science, technology and higher education minister, who spoke to Science and highlighted plans to work together both on COVID-19 and climate change, including aims to build several joint programmes with the US under its new administration, including inviting them into Horizon Europe. On January 11th the European Council of Foreign Relations even published a commentary on how Biden’s longstanding relationship with the Balkans, paired with the EU’s work there could be transformative for the region.

There are still several hurdles to the revival of transatlanticism. For one, while Biden has expressed hopes to utilize the transatlantic relationship to counter China, the EU recently signed a landmark investment agreement with Beijing. Although this agreement in and of itself does not directly threaten transatlanticism, even if it is a bit of a slight to Biden, it does speak to possible issues in this arena. The pro-U.S. bloc against-China strategy has the potential, if pushed by Biden, to cause further divisions within Europe because many Central and East European countries rely on China’s financing or export market.

In addition to how to deal with China, Carnegie Europe highlights technology as a key issue on which the EU and US do not see eye to eye because of data privacy and competition tensions. This is one of the areas the Portuguese presidency has highlighted in their action items. There is some hope for cooperation on this front as the incoming US administration seems willing to start reigning in Big Tech. Additionally, in terms of monitoring, big changes have already been made ahead of the Biden inauguration and in response to the events of January 6th. Sitting President Donald Trump has been banned from a wide variety of platforms including Twitter and Facebook. The app which his supporters have been using to communicate uncensored, Parler, has also gone offline after Amazon kicked it off its servers. Regarding the revival of democracy both the US and the EU, especially certain Member State governments have a long way to go. In terms of major trade deals, constituencies on both sides of the Atlantic seem to have lost their appetite.

Finally, there is the future to consider. Fears that someone ideologically closer to Trump than Biden may claim the US presidency in four years and undo hard work on the transatlantic relationship “could inspire strategic hedging on Europe’s part”, writes the Economist. The sheer number of Americans who voted for Trump, the continued and popular environment of questioning the election results, and the recent violence at the Capitol stoke rather than quell these concerns.

Events leading up to and following Biden’s inauguration will likely impact this further. If things are relatively calm and Americans seem to fall in line behind Biden, EU leaders will be more prone to trust. The second impeachment of Trump, with supporting votes from 10 Republicans, what seems a possible conviction in the new Senate after inauguration, and the attitudes of various GOP officials brings some hope to this route forward. Alternatively, if mass demonstrations against the incoming President continuously break out and are hard to get under control, one can expect further wariness from across the Atlantic.

Follow the comments: |

|