Manipulation of information is not a recent phenomenon, quite the opposite actually. The first dictator of Ancient Greece, Peisistratos, had faked his own attempted murder in order to be given bodyguards, who eventually helped him take power over the Acropolis in 561 BC. So why have we waited so long to characterise and give a name to fake news? The internet and social media have played a decisive role in giving fake news unprecedented visibility. Not only do they spread massively and instantaneously, but also the internet’s accessibility has allowed an infinite multiplication of information sources. Today, anyone can produce information: traditional media, a blog, but also a mere witness on social media. A monopolistic or top-down way to produce information thus no longer exists.

According to Nicolas Kaciaf, senior lecturer at Sciences Po Lille, veracity is no longer the equivalent of official information: “concerning Donald Trump, we can see that American journalists consider that official speech cannot be trusted anymore”. Moreover, the level of sophistication of fake news is so high that, for some people, they have become as credible as traditional media, especially as the general context of mistrust towards traditional media favours fake news. According to a study by Le Soir [1], the Belgians’ trust towards the press has been reduced by 50% in 20 years, falling from 42% to 21%. For its editor-in-chief Christophe Berti, “the debate is no longer objective, backed up by sources, argument against argument, but rather accusation against accusation”. Fake news’ virulence and the astonishment that they arouse make people talk. Spreading by word of mouth, fake news manage to enter reality, which reinforces an impression of truth.

Change in the users’ behaviour has also contributed to the entrenchment of fake news. By only informing themselves via social media without checking the information’s veracity, some users lock themselves into a vicious circle. What the groups of friends post and share often goes along with what we already think. This creates an environment that determines who an individual will trust. The targeted by a fake news can of course refute a story, like Obama who had showed his birth certificate to prove that he was born in the USA. A plagiarised traditional media can officially deny, like Le Soir. But these are case-by-case measures. How can we overarchingly tackle fake news?

The German example

Germany is the only European country to date to have established a piece of legislation on fake news, named ’NetzDG’ and entered into force on 1st January 2018. The new law obliges social media to delete hate speech within 24 hours, including fake news, at risk of being fined up to 50 million euros. For more complex cases, however, a delay of 7 days or more can be given.

For the German Minister of Justice Heiko Mass, “defamation and malicious rumours do not fall under freedom of expression”. However, for Human Rights Watch, this law would break the respect of freedom of expression. The NGO considers that determining whether words are subject to law or not, in addition to very short review periods at the risk of paying heavy fines, is so difficult that it would encourage companies to delete content that is still probably legal. Moreover, the law does not foresee any control or judicial remedy. The German Federation of Journalists (DJV) denounces the fact that “an American-based private company can decide limits to press freedom and to freedom of expression in Germany”.

The French legislative proposal

On 3 January 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron announced in a press release that a bill to tackle fake news would be drafted before the end of 2018 and called “law on the confidence and reliability of information”. The law would particularly target the news that spread during electoral periods so that votes would not be influenced. Thereby “in the event of the propagation of fake news [during the election period], it will be possible to bring the case before a judge through a new interlocutory proceeding, allowing if necessary to delete the concerned content, to remove references to the website, to close the concerned user’s account, and even to block access to the website”.

However, for Gérad Larcher, President of the French Senate, this is not enough: this law should be extended beyond electoral periods. But criticisms can also be heard the other way round. Two existing laws would already be capable of sanctioning fake news. The electoral code allows to sentence “those who, using fake news, slanders or other fraudulent tactics, would have caught or distorted the votes, determined one or several voters to abstain from voting”. Moreover, article 27 of law of 1881 on press freedom foresees a fine of up to 45,000 euros in the event of “publication, spreading or reproduction, by any means, of fake news […] when, done in bad faith, would have disturbed the public peace, or would have been suspected to do so”. As in Germany, the respect of press freedom is being questioned. Edwy Plenel, founder and president of Mediapart, opposes such a legislative proposal: “We are at the heart of a freedom which does not belong to the executive power […]. Freedom doesn’t need the state to interfere”.

Towards a harmonised European legislation?

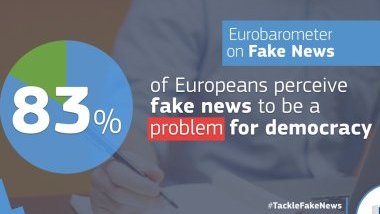

In 2017, worried about the situation, the European Parliament asked the European Commission to analyse the current European juridical framework related to fake news. The Parliament would like to know if possibilities of legislative intervention exist to limit the publication and spreading of fake news.

In November 2017, the European Commission launched a three-month “public consultation on fake news and online disinformation” via an online platform accessible to all EU citizens. The objective is triple: measure the problem’s extent, assess the already experimented measures, and think about future actions. Concretely, the questions were diverse: Have you ever been confronted with fake news? Via which media have you encountered the most fake news? Do you think that more needs to be done to reduce the spreading of online disinformation? This consultation’s results were then used for the EU reflection on the subject.

A group of 40 experts is working on fake news and online disinformation. The team is composed of social media and platform representatives including Facebook, Twitter and Google, of journalists from the AFP group, Mediaset and Sky News, of academics and of consumer representatives. According to Mariya Gabriel, European Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society, “it is not about sorting ’good’ and ’fake’ news, but about understanding the phenomenon as a whole”. The goal is to gather as much information as possible to then advise the European Commission through assessing successful measures, defining roles and responsibilities and making recommendations. The four central points are transparency, diversity, credibility and inclusiveness. The aim is not legislative, but rather about information, debate, “a frank and open discussion”. The Commissioner also affirmed her “engagement for freedom of expression”, stressing that “no one intends to constrain citizens in believing or not believing in a particular piece of information”, and refuting the idea of a “ministry of truth and censorship”. The report was published in March 2018.

Outside of the legislative framework, more and more solutions have been developing: the anti-fake news filters developed by social media themselves, fact-checkers created by traditional media such as Le Monde’s Décodex in France, or preventive measures within schools. The latter method is even the one recommended by Edward Snowden:

“The problem of fake news isn’t solved by hoping for a referee but rather because we as participants, we as citizens, we as users of these services help each other. The answer to bad speech is not censorship. The answer to bad speech is more speech. We have to exercise and spread the idea that critical thinking matters now more than ever, given the fact that lies seem to be getting very popular.”

Follow the comments: |

|