On November 23rd 2020, French police violently dismantled a makeshift migrant camp in the heart of Paris, clashing with migrants and activists, who were protesting the profound lack of accommodation and infrastructure for the country’s refugees and immigrants. Images of French police officers violently removing the protesters turned the spotlight once again on the country’s issue of police brutality. It is not the first time that human rights groups have condemned the police’s behaviour as thousands of migrants and migrant rights advocates took to the streets of Paris to protest the police’s discriminatory practices last November.

The November protests were French citizens’ way of denouncing continuous police discrimination and eviction of migrants from camps and settlements, leaving them homeless and without any option but to seek refuge in forests and under bridges. The protesters demanded the opening of accommodation for all migrants and the implementation of a consistent reception system, highlighting a broader issue of mistreatment of migrants and refugees reflected in the state’s harsh immigration policy. These protests were met by police brutality and violence. Nevertheless, such allegations of police violence are not unprecedented in France; yet they are extremely alarming. France has a history of police brutality with police violence and discrimination having structural roots. At the same time, recent allegations of discrimination of human rights by the police forces have been extremely frequent. In fact, since the appearance of the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) movement in December 2018, and with the recent demonstrations and strikes against pension reform, the question of police violence in France has entered the mainstream and is at risk of becoming the norm.

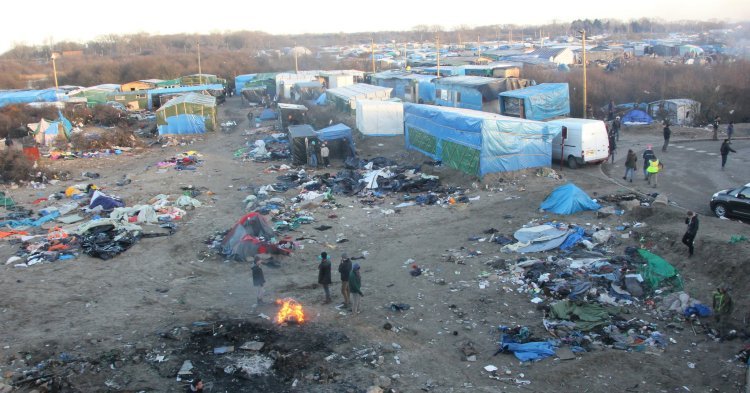

This systematic police brutality has been deliberately targeting refugees and migrants, drawing attention to France’s overall treatment of these groups. To better comprehend this issue, one can look at stories of refugees from Calais. The refugee camp of Calais, also known as “Jungle”, at its peak in 2015 had become a semi-permanent slum, housing approximately 12,000 asylum seekers as men, women and children fled en masse to Europe. But following its destruction in October 2016, and subsequent efforts to prevent the formation of a permanent migrant accommodation site, the camps are now a tenth of the size and scattered into fragments across the city and its suburbs. Nowadays, humanitarian charities are raising the flag, claiming that the conditions faced by refugees in the whole of northern France are now more precarious than ever, also owing to the ongoing global health crisis. Reports from humanitarian organizations shed light on curbs imposed by the French state against aid for refugees, charities being banned from distributing food in the city centre of Calais and the use of excessive police force against humanitarian workers while they carry out their work. In Calais, violence and police harassment are commonplace. These moves are just examples of France’s broader campaign to hinder humanitarian aid, thus, proving its failure to deal with the refugee crisis.

This hostile treatment extends far beyond targeting NGO work and humanitarian workers and pervades the daily experience of refugees, through evictions, confiscation of possessions and arbitrary identity checks in the street. Those checks recently took a more alarming turn in Grande-Synthe, Dunkirk’s refugee camp, when several refugees, including those working as volunteers for a charity, were prevented from entering a supermarket. Moreover, most of numerous evictions that have been carried out the past year are based on ‘flagrance’, a measure which allows police to remove occupants of private land if there has been a complaint and they have been there for less than 48 hours. Some of these evictions lead to arrests and deportations but are proven ineffective as often refugees flee and later return. Most recently, police were reported to have cut down and thinned out trees in the few places left where the refugees sleep in Calais.

The government’s treatment of refugees is part of an inefficient and inhuman political agenda that has worsened since Gérald Darmanin became France’s Minister of the Interior in July 2020. Despite the French government claiming that these actions adhere to the country’s laws and international legal obligations, it can be easily argued that they constitute an abuse of the system. Human rights groups consider these actions illegal and argue that politics of repression, violence and harassment has been going on for years. Lawyers say the evictions are harassment and a breach of UN and French human rights law, with this emergency measure of ‘’fragrance’’ – intended for gathering facts about a crime – deployed wrongly and permanently. Under normal circumstances, an eviction requires the authorisation of a judge, a social diagnosis to identify vulnerable people, and preparation to provide rehousing solutions. But under ‘’flagrance’’, which should be a short-term measure, there is no legal basis and no opportunity to appeal.

Although police brutality in France is not a new phenomenon, recent events raise concerns about the future of human rights in the whole of the European Union. Such incidents of widespread discrimination and deeply rooted police violence have alarming effects not only for France but for the whole of Europe. They should not be treated as isolated events but as part of a regular phenomenon that threatens the European principles of rule of law and respect of human dignity. Calais is just a form of experimentation. Discriminatory policies are being now tested in Calais and all over France, and will likely have implications for the development of security policies across the Eurozone. If these practices are not met with contestation and resistance, they will be normalised and used as ’’success stories’’ for future security policies, likely to be adopted elsewhere. Therefore, France should respect its human rights obligations and ensure the respect of the rights of migrants and asylum seekers as well as provide human and dignified treatment. Instead of authorising police officers to confiscate tents in the middle of the night, French authorities should guarantee the provision of safe accommodation and respect the dignity of those on the streets. The need for an alternative approach in immigration policy is more pressing than ever, at a time when opinion polls clearly show that French voters are concerned about the issue of migration turning them to support far-right leader Marine Le Pen. It is about time that the country of liberté, égalité, fraternité lives up to the expectations derived from its inspirational history and positively influence European policy for the respectful treatments of migrants.

Follow the comments: |

|