“What! Because we are poor, shall we be vicious?”

– John Webster, English dramatist of the 17th century

Ever since the times of old, poverty has been coupled with corruption, just as bad hygiene is linked to the spreading of disease. At the same time, those below a certain level of material wealth were not considered “full citizens”, having, as a result, fewer rights – or none at all – within the polity when compared with the propertied citizens.

In scouring the nooks and crannies of society, economists came to a conclusion: for every individual, there are only two ways in which to obtain wealth – to increase the size of the “pie” (to create wealth) or to carve up a large piece of it for oneself (to redistribute existing wealth).

But creating wealth out of nothing is, and always has been, a titanic task. Redistribution, another impossibly complex method, becomes however immeasurably easier when it is done for the benefit of one person, or even a few. For that reason, those in positions of power have always been tempted to use their office in order to enrich themselves and their associates.

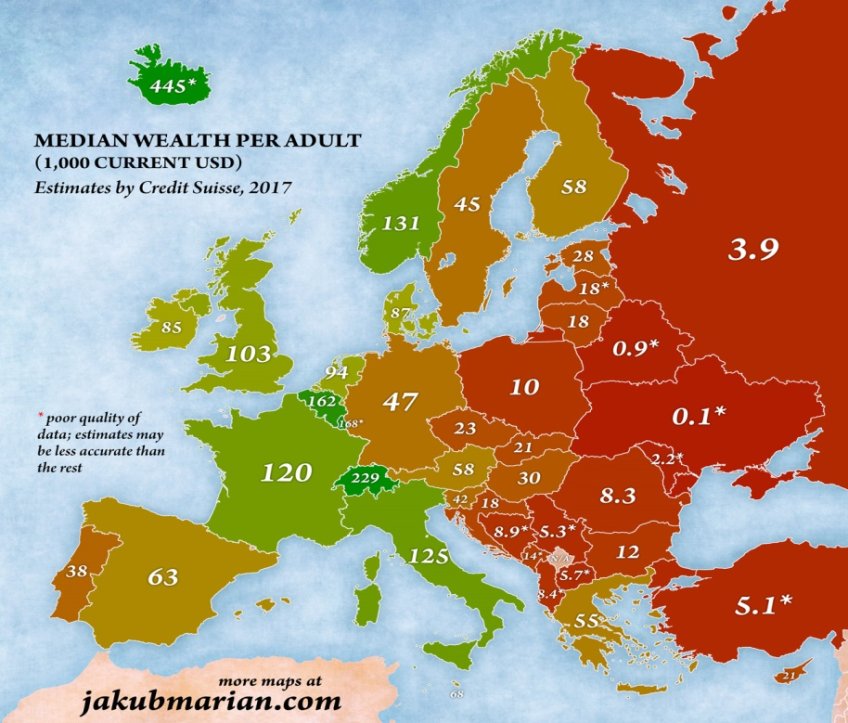

Europe, of course, has not been immune to either corruption or poverty. Maps outlining the status of every member state of the EU, however, highlight an important difference – corruption and poverty are greater in Eastern European countries than in the West or North of the old continent.

According to Transparency International, Romania, for example, ranks 57th out of 176 on the corruption perceptions index of 2016, with a score of 48/100, 0 being very corrupt and 100 very clean.

Day-to-day realities in Romania confirm the standings. In May 2016, it was revealed that the third largest producer and distributor of medical supplies, catering to hospitals and hospices all over Romania, had heavily diluted its disinfectants, knowingly exposing patients to disease and infection. Although SRI, the Romanian Intelligence Service, had sent 503 informative notes on the company’s misdoings to the authorities, nothing happened due to its patron’s political connections, who later died – or committed suicide – in a car accident.

The Hexi Pharma scandal is but one example, albeit gruesome in consequences, in the way that corruption manifests itself in Romania. From the meekest clerk that can “speed up a file” in return for a “small attention” to the leader of the largest political party in the country and his ministerial acolytes, corruption is but another part of a thoroughly accepted system of unspoken laws and practices, as natural and as unstoppable as the common cold, except all year round.

Many – if not most – Romanians have long accepted that the “clever guys” that have ruled the political stage will never be punished, that public funds will usually go to friends and associates of those who decide how to spend them, that knowing-someone-who-knows-someone is the way to go. They have long accepted that even in the supposedly free marketplace that was adopted after 1989, competition is not free and fair, but watched over by heavy-handed regulators that would stop visiting your place of business if you would just give them some money.

In the post-communist societies of Eastern Europe, homo faber, the creator-humans of Henri Bergson, were quickly overtaken by Hannah Arendt’s animal laborans, the “laboring animals” who “create nothing of permanence, whose efforts are quickly consumed, and must, therefore, be perpetually renewed so as to sustain life.” They were the slaves of the immediate tomorrow, of basic, constant needs. The same dominating necessity is even worse for those who live with the sword of poverty above their heads, and it has not changed since then. Every act you make, every good you buy or service you pay for, they all taste and feel differently when experienced at the edge of vagrancy.

As a societal phenomenon, poverty remains pervasive where individuals decide that self-directed redistribution of wealth, and not its creation, is well worth the risk when compared to – ironically - poverty. Eventually, however, the only thing to redistribute is a lesser degree of the very thing they were attempting to avoid – poverty. Corruption, to most men, is the result of a cynical acceptance of poverty, the absence of any hopeful general improvement, and finally a realization that salvation is individual.

*Wealth is understood as financial and non-financial assets minus debt.

Scholarly literature of democracy and democratization has long praised the middle class as the promoter of liberal-democratic values. By comparison, dictators and autocrats such as Argentina’s Juan Peron or Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez have often used the poor masses (“descamisados” – the shirtless) in order to rule. Even in relatively stable democracies such as Romania and Bulgaria, the poor are “bribed” with goods in order to vote in a certain way.

If society treats you as less of a citizen, with fewer rights, why should you act otherwise? It therefore becomes perfectly rational, under an ineffective and immoral state, which is biased towards wealth, to employ every means – legal or illegal – to obtain money, goods and status, which in turn ensure your safety under the corrupt state.

Ergo the monster of corruption, a societal product, made out of the resentment of the poor for the state, out of desperation, opportunism, political ignorance and out of the self-vindictive justification that nothing is out of moral bounds because there are no moral bounds.

However, the answer is not a greater redistribution of the “pie” towards the infuriated many. This can only quench their thirst for so long, and will, in the end, reach the same dead point that a thoroughly corrupt society would – the redistribution of poverty. Another ineffective method is to constantly make up administrative tools to fight corruption, such as the European Union has done. This is yet another weed that distant bureaucracies cannot exterminate.

Instead, salvation – although necessarily collective – remains an individual choice. Are you to be the only honest man in a corrupt society? Will you suffer underserved poverty and humiliation, with no way of advancement, just for the sake of what? Honesty? Morality? The good nature of man? Will you be the only one dining on bread, when so many others feast?

All we need is one person who will face the others and answer: “If need be.” At that point, corruption is vanquished. Until that time, it remains the job of daring prosecutors to do what we cannot - make ourselves and others honest through fear of the law.

Follow the comments: |

|