The domestic politics: Brexit means hard Brexit

Theresa May is under intense pressure from Eurosceptic elements within the Conservative party and the electorate. Leavers were worried that the UK might engage in a Brexit that would not allow the country to “take back control” of its sovereignty. While doing the latter is illusory in today’s globalised world, it has nonetheless been the cornerstone of the Leave campaign. Going back on yet another major promise – after the £350M promised to the NHS that never existed – would be politically damaging for the Conservative party and those associated with the Leave campaign. To calm these fears and others’ – notably from the markets – Theresa May made three main announcements in a speech. Article 50 TEU will be triggered no later than March 2017. This buys the relevant departments some time to recruit negotiators and begin to prepare themselves for what may be the most complicated deals the UK has ever had to negotiate. A “Great” repeal bill will free Britain from the shackles of EU regulations and the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction in Britain will cease. The UK will not “give up control of immigration ... again”, indicating May is leaning towards a hard Brexit: these goals are incompatible with a soft Brexit, i.e. continued participation in the Single Market. David Davis, the UK’s Brexit Secretary, while dismissing the difference between hard and soft Brexit, agrees that the goals are regaining control of borders and law-making, and the “best possible access” to – not participation in – the Single Market. That way, according to him, there will be “no downside to Brexit at all”, only “upsides”. Trade Secretary Liam Fox even wants to leave the EU customs union in order to trade with the rest of the world. The Commons’ challenge to the Government is noteworthy: granted, 52% of the electorate voted Leave, but a hard Brexit has not been decided democratically – most Scots and Northern Irish will agree with this. In fact, it may be that a majority of Britons would rather keep the UK’s participation in the Single Market to the detriment of “taking back control” of the borders. It would therefore make sense that MPs would have a say over the process of Brexit. This is dismissed by the (unelected) Government, however, as attempts to hijack democracy and the will of the people, and no “running commentary” of the negotiations will be given. The verdict of London’s High Court – in favour of MPs – has already angered Brexiters that portray the Court’s judges as “enemies of the people”. The government will also appeal to the Supreme Court. At any rate, just how much influence MPs will yield over the process of Brexit remains to be seen.

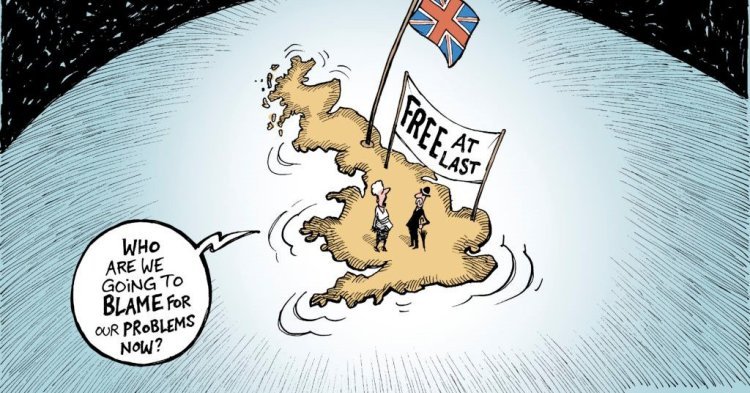

The international politics: has time for a soft Brexit run out?

Across the Channel, this rhetoric – and the UK’s attempts to bend the rules, dismissed by Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson as “baloney”, by insisting on pre-article 50 negotiations, conducting pre-Brexit trade negotiations with third countries, and suggesting it will veto any decision by the European Council until formal Brexit – are pushing the EU and Member States towards more extreme positions. And of course, suggesting that businesses not employing enough British workers could be “named and shamed” (a proposal that was later withdrawn) and that EU nationals in the UK are “cards” in the negotiations is not conducive to an atmosphere of goodwill in continental Europe.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has advised EU leaders to be “intransigent” with London. ALDE party President Guy Verhofstadt, who will be representing the European Parliament at the negotiations, is likely to be uncompromising regarding the EU’s rules and values. French President François Hollande understands that “the UK has decided on Brexit, [he] think[s] even a hard Brexit” and warns that there must be a price, a threat, something negative that would encourage other nations not to emulate Brexit. He may not be re-elected in 2017, but most of his opponents – bar populists – are likely to maintain that stance. Yet the strongest signal of a shifting mood might have come from across the Rhine. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, herself facing elections next year, but with high levels of support and no credible opponent, has pressed businesses – expected by Leavers to push for a favourable Brexit at the expense of the EU’s values – to refrain from doing so.

Perhaps the best argument for why a hard Brexit is likely, may be that a soft Brexit is very unlikely: in the absence of pre-art.50 negotiations on substance, there are little incentives for May’s government to change its stance before March 2017. Although UK business will ask for a soft Brexit, it might be dismissed as coming from the rootless and greedy “international elite” framed in May’s speech. Even the issue of the Irish border may not be enough to deter Eurosceptic elements from jumping off the cliff. Once the negotiations begin, Britain will have two years to negotiate several deals. This is already a very, very tight timescale, and it seems very unlikely that the UK would go back on the repeal bill, immigration control, and the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction, as this would constitute a political humiliation domestically. All the more since a soft Brexit is in fact some sort of EU membership-light, but without any decision making power nor ability to prevent an EU federal state – that exists only in some Brexiters’ nightmares and some pro-Europeans’ dreams – from taking shape. Norway and Switzerland are not necessarily inclined to “share” their model with the UK, since that would risk changing it. Finally, should the negotiations, especially on an interim deal, fail to be completed in two years – for lack of time, or simply lack of agreement among the 27 – the hardest of Brexits will fall down on Britain: no Single Market access, no trade deals with anyone, no WTO membership...

Follow the comments: |

|