What is the externalisation of asylum? The Australian model

For almost 11 years now, Australia’s offshore handling of asylum seekers has gained international attention and has been regarded as a role model by some or as a breach of human rights by others. On August 13th 2012, the country’s government put into place a migration policy that consists of sending asylum seekers that arrive in Australia to detention centres in other countries. Papua New Guinea and Nauru have been the two destinations. Nauru is a small and remote island 4500 km from Australia; its surface is 21 km2, which is a bit smaller than Frankfurt’s airport.

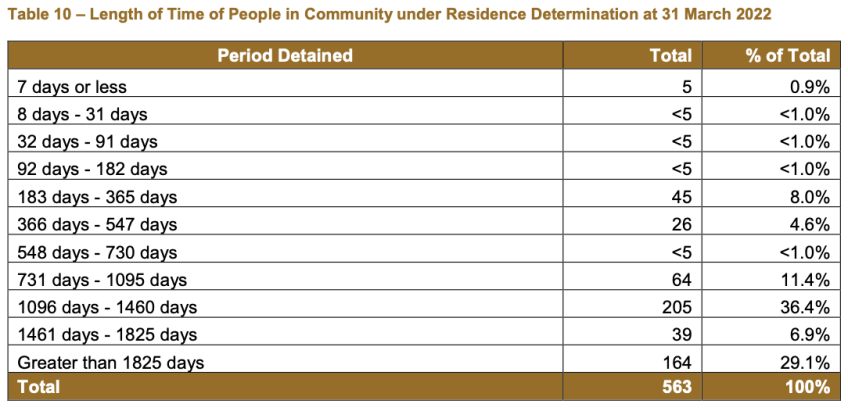

The measure is directly aimed at discouraging asylum seekers from reaching the country. According to the latest data made available by the Refugee Council of Australia, 4,183 people have been sent to offshore detention centres. Various human rights organisations have criticised the inhumane conditions of such practices, having caused the suicide of seven people and traumatic experiences for thousands of people, including many children. Such actions violate international law, which determines that detention centres for migrants “should not be used as punishment but rather should be an exceptional measure of last resort to carry out a legitimate aim”, explains a Human Rights Watch report. The organisation highlights that adults should be kept for the shortest time possible and children should not be placed in detention at all. However, as of March 2022, the average detention time in these centres was 700 days, based on data provided by the Australia Department of Home Affairs.

Duration of the stay in offshore camps, source: Home Department, Australia

The International Criminal Court and UNHCR have condemned the Australian model for keeping asylum seekers detained for long periods of time and keeping them in conditions that pose a risk to their physical and mental health. Besides the human rights breaches it entails, the model has proved ineffective and extremely expensive. Human Rights Watch estimates the price for detaining one single person at 3.4 million AUD (2.08 billion EUR). Villads Zahle, Head of Communications at the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), explains why the costs are so high. “Australia has been able to provide financial incentives to impoverished Pacific states in its near neighbourhood to host people. The model has been extremely expensive - far more costly than simply managing asylum applications in Australia - and has led to a series of violations of human rights, along with enduring basic cruelty”. And yet, the core idea seems to find emulators all around the world.

Offshore handling of migrants: Can it happen in Europe?

The criticism has not discouraged other governments from looking up to the Australian migration policy. In Europe, the Australian model has inspired countries for which migration policies are a major priority. The first one to take the issue far enough to contemplate the offshore relocation of asylum seekers was Denmark. In June 2021, the Danish government passed legislation introducing the possibility of relocating asylum seekers to third countries outside of the EU while their cases are reviewed. According to the legislation, this would mean the chosen third country could assess the asylum requests, with the applicant potentially receiving refuge there.

The law established in 2021 did not specify which country would host the centre or give refugee status to the applicants. The possibility of opening detention centres in Rwanda was discussed, but since a new Danish left-right government led by the Social Democrats took office in December 2022, the talks with the African country have now been suspended. The new Danish government has the same ambition as the previous one but wants to use a different process by establishing a reception centre outside Europe in cooperation with other countries.

Following in Denmark’s footsteps, the UK proposed an “Illegal Migration Bill” early last March. The bill, which is heavily inspired by Australia’s refugee policy, contemplates a stricter handling of asylum seekers entering the country. If passed by the Parliament, the bill would deem all asylum seekers arriving in the UK without a visa as “illegal”, which, in turn, would make it impossible for them to apply for protection. Among other things, the proposed document introduces the possibility for anyone arriving “illegally” in the UK to be sent back to their country of origin or a “safe” third country. Like in Denmark, the UK has started negotiations with Rwanda and has even put in motion a plan to build at least 1,000 houses for the asylum seekers sent to the African country if the five-year trial of the plan is approved in the courts. While legal procedures are still ongoing, all flights are prohibited from taking off to Rwanda with this purpose.

With the stated objectives to “put a stop to illegal migration into the UK” and “speed up the removal of those with no right to be here”, the bill would have to be passed by the Parliament in order to become law. For now, the draft legislation has faced significant backlash from refugee charities and international figures alike. In a recent letter to the House of Commons and the House of Lords about the “Illegal Immigration Bill”, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović expressed her concern about what the passing of the bill might mean for the well-being of migrants and the prevalence of “well-established and fundamental human rights standards”.

People are tired of seeing small boats arrive in this country with the authorities appearing helpless to stop them.

Read my plan to tackle illegal immigration in today’s @TheSun https://t.co/K5fzFSNWtH

Sign up to the campaign: https://t.co/3cXn1rFhca pic.twitter.com/gQ9vQS3mlQ

— Rishi Sunak (@RishiSunak) July 24, 2022

Next steps

The passing of the bill is also dependent on an international agreement on the matter of legal routes to Great Britain and the question of returns. For one, there’s the bilateral relationship between France and the UK to be taken into account, as the English Channel is the most common route taken by migrants attempting to reach the island. On the other hand, the European Union and its laws have to be taken into consideration. In this regard, France’s interior minister Gérald Darmanin talked about the importance for the “European Commission, Great Britain and, of course, [EU] member states” to reach a collective agreement on this issue.

Both the Danish and the UK’s attempts are the furthest any country in Europe has ever gotten at externalising asylum processing. On a smaller scale are failed ideas and plans that have come from countries like Israel or Austria in recent years, some having gained some traction after the recent developments, says Villads Zahle, Head of Communications at the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). According to Zahle, these externalisation attempts are a cause of frustration for other European countries but, ultimately, unlikely to be fulfilled.

When asked about the reasons why Europe’s next steps towards externalisation of migrants might lead to nothing, Zahle also referred to the lack of incentives, other than economic, for third countries to engage in the process. “The centres are extremely expensive and practically and logistically challenging/impossible, so there is no appetite from the European Commission” he said. Other than that, “outsourcing of asylum processing fails because they violate European and international law” the ECRE Head of Communications added.

Is externalisation of asylum legal?

During a recent press conference, ECRE Director Catherine Woollard talked about whether externalisation procedures are in line with European and international Law: “Proposals for external processing of asylum applications re-emerge regularly. But it never happens because the legal, political and practical obstacles are extensive.” According to Woollard, the idea of externalising the asylum process is “unworkable”.

From the European law standpoint, offshore detention centres are largely regarded as a breach of a number of human rights principles. After the announcement of first flight taking asylum seekers from the UK to Rwanda early last year, the European Court of Human Rights openly condemned the decision by stating that it should be stopped under Rule 39 of the Rules of Court. If “offshoring” comes into play as a general practice, we would also be talking about the violation of the asylum seekers’ right to access justice contemplated in Articles 6 (1) and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The implementation of these policies would also bring up concerns related to the safety conditions of the third-country detention centres.

In Germany, the so-called “Traffic Light Coalition” has been reported to contemplate the possibility of transferring migrants, mostly asylum seekers rescued in the Mediterranean, to North-African countries for processing of their asylum claims. However, advances in this direction have met opposition from civil society and European NGOs. “[In Germany], external processing of migration was pushed into the coalition agreement during the formation of the current government” says ECRE’s Zahle, even though according to him, the German assessment will probably “lead to nothing”.

What are the alternatives?

Externalising migration has already proved to be extremely abusive and dangerous for migrants, as well as inefficient and costly. So, what should governments do instead?

“Rather than wasting resources on vague and unrealistic proposals for external processing which never work, Germany would be better off supporting efforts to make asylum function in Europe. As well as improving its own asylum system, Germany has a strong direct interest in ensuring better implementation of EU asylum law across Europe as a whole, and by all countries”, suggests Zahle on the German case.

Instead of sending asylum seekers to non-EU countries, some solutions might be higher investment on national systems and better coordination across European countries. In addition to the disregard for human rights it implies, the Australian model has proven to be inefficient and extremely expensive. And while debate around the topic is still ongoing in Europe, it seems unlikely that offshore handling of asylum seekers would be implemented anytime soon.

This article is part of the project "Newsroom Europe" which trains young Europeans from three EU Member States (Germany, Sweden and Spain) in critical and open-minded media reporting and on the functioning of European decision-making. The project is carried out jointly by the Europäische Akademie Berlin e.V., the National Museums of World Culture Sweden, and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation Spain, and is also co-financed by the European Union.

Project partners “Newsroom Europe”

Follow the comments: |

|